Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsSoutheast Asia remains unfriendly for women in politics

A recent report exposing the growing violence targeting woman parliamentarians in Southeast Asia serves as a clarion call to create a regional protection initiative for lawmakers at risk, as well as facilitate their inclusion and empower their voices toward gender equality in politics: a fundamental principle of democracy.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he 2025 report from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) paints a chilling portrait of political life for women in the Asia-Pacific: Three in four women parliamentarians have endured psychological violence, and one in four has been subjected to sexual violence. Far from isolated incidents, these acts form a disturbing pattern of abuse targeting women for daring to lead. Violence, both online and offline, has become an entrenched feature of public life for women in politics.

More than 60 percent of women in political office have been victims of online hate, threats and disinformation campaigns. Parliamentary staff, especially young women, are similarly vulnerable. These attacks are not random: They are deliberate, systematic efforts to degrade, silence and push women out of politics.

This is not just a gendered struggle; it is a profound democratic crisis that erodes the very foundations of inclusive governance.

These concerns were echoed at the 6th Members’ Forum of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) in December 2024, where lawmakers from across Southeast Asia raised the alarm on the rising tide of violence against elected women leaders.

From online abuse and legal harassment to surveillance and judicial persecution, the threats are not only multiplying; they are becoming normalized. Women parliamentarians are not just targeted for what they say; they are punished for daring to participate in politics at all.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the case of Thai parliamentarian Chonticha Jangrew, who is currently facing 28 legal cases alongside a relentless wave of gender-based online harassment. Her “offense”? Speaking out against authoritarian laws and advocating for democratic reform. Her presence in politics is considered a threat because she dares to speak, question and lead.

Before taking office, she was eligible for support from international human rights organizations. But as a sitting member of parliament (MP), she now inhabits a legal gray zone. Thai law restricts the ability of lawmakers to receive outside assistance, leaving her without access to legal aid, mental health services or personal security: an alarming gap for any elected representative, let alone one under sustained attack.

This vacuum of protection is not unique to Thailand. Elected officials across Southeast Asia, especially those aligned with pro-democracy and human rights movements, find themselves isolated and exposed. Legal frameworks fail them. Political institutions ignore them. Even their own parties sometimes abandon them. The result is a chilling effect on women’s political participation and a warning to others who might consider following the same path.

This repression is not always overt. Tactics like red-tagging – falsely labeling women politicians and activists as communists or terrorists – have become dangerous tools of political control. Especially common in the Philippines and parts of Indonesia, red-tagging is a particularly insidious form of gendered political violence. Women are painted as enemies of the state for advocating reform and subjected to surveillance, threats or even extrajudicial violence.

These are not merely smear campaigns; they are deeply political strategies of exclusion. Red-tagging has been used to justify legal persecution, public vilification and even lethal force. Women who advocate for human rights, indigenous rights, environmental protection or peace-building are disproportionately targeted. The aim is not only to discredit, but also to delegitimize and endanger them.

APHR’s annual reports on MPs at risk from 2020 to 2023 underscore this reality. Women leaders are often met not with debate, but with abuse: threats to their safety, dignity and even their families. The vitriol follows them from the campaign trail to the legislature, with digital platforms acting as megaphones for hate.

And yet in the face of this relentless hostility, women continue to rise. They campaign. They legislate. They resist.

Their resilience is reshaping Southeast Asia. In Myanmar, women lead pro-democracy efforts under the shadow of military rule. In Indonesia and the Philippines, female lawmakers and activists are challenging disinformation networks and patriarchal norms. These women are not just survivors; they are trailblazers.

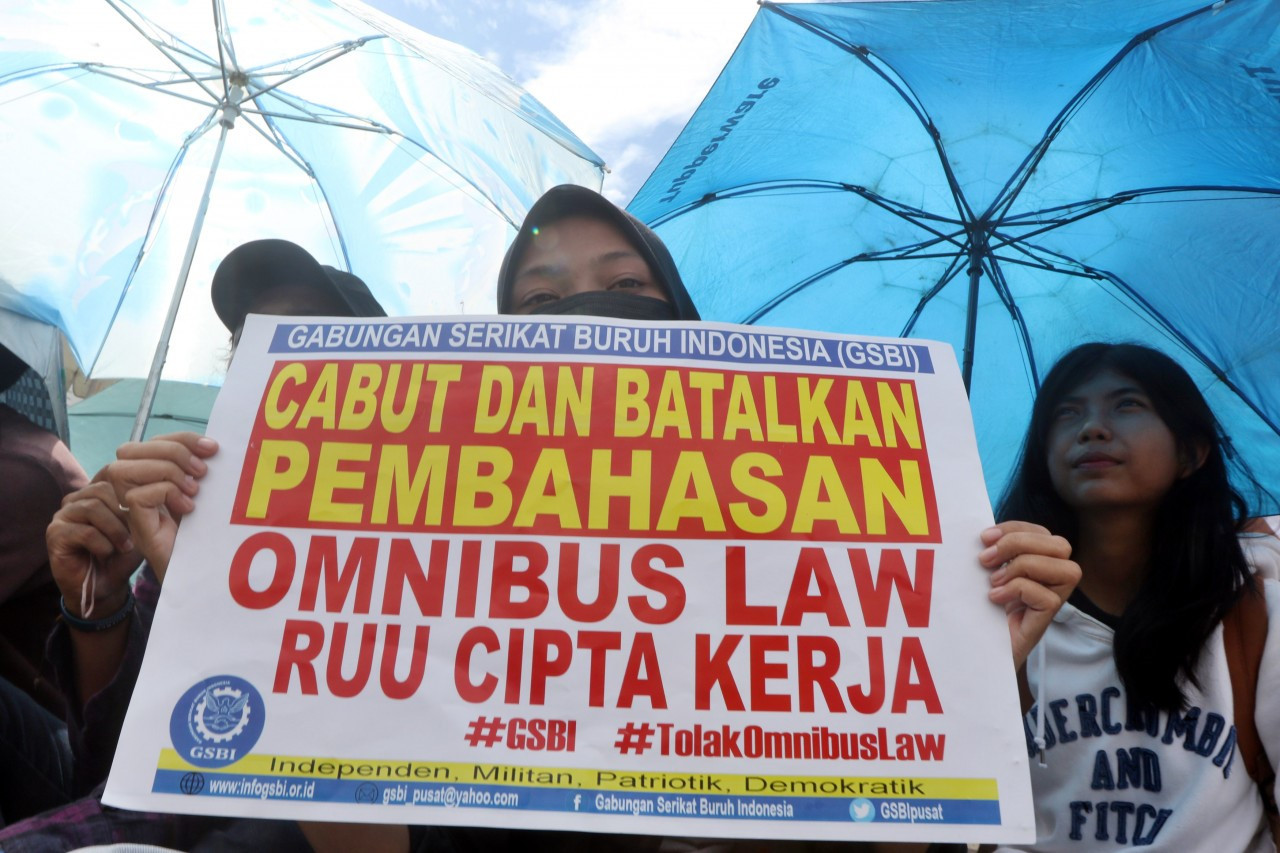

Signs of progress are emerging. In the Philippines, efforts to institutionalize safe workplace policies in parliament are gaining traction. In Indonesia, the long-delayed Sexual Violence Bill was passed, thanks to years of relentless advocacy led by women across political lines.

These victories, though hard-won, demonstrate what is possible when women lead and when institutions listen. ASEAN must now follow suit by adopting regional standards to combat online violence and uphold digital safety.

We must believe that a different political culture – one that embraces, not fears, women’s leadership – is not only possible, but necessary.

International solidarity and diplomatic presence remain vital. External attention can serve both as pressure on authorities and as protection for those under threat. Institutions like the IPU and United Nations mechanisms must continue monitoring the situation and supporting at-risk parliamentarians.

As technology accelerates the violence through harassment, deepfakes and disinformation, the digital space can and must be reclaimed. With strong laws, ethical platforms and political will, technology can be used to empower women in politics, not exclude them.

Governments must act decisively to criminalize technology-facilitated gender-based violence. Social media companies must be held accountable for enabling abuse. Political parties must foster inclusive environments while legislatures must create internal accountability mechanisms to protect their members, especially those under attack.

To address these urgent gaps, there is a need to establish a regional protection initiative for MPs at risk, one that facilitates legal, mental health and security support to elected officials facing violence and intimidation due to their human rights advocacy. It is a necessary step toward building real safety for those at the frontlines of democratic resistance.

If Southeast Asia is to deepen democratic norms, then protecting those who dare to represent the people must be a core priority. The region cannot afford to lose its boldest voices to fear, repression or exile.

Ultimately, the fight for gender equality in politics is not just a matter of fairness; it is a test of our democratic commitments. A democracy that silences half its population is no democracy at all.

***

The writer is executive director of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR).