Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhen the benefit of the doubt runs out

As we look ahead to the legislative and judicial changes in 2026 with one eye toward the 2029 polls, perhaps it is time for the people to rethink what the current administration has accomplished with the sovereignty, political legitimacy and leeway we have granted it.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

ndonesians may wake up in 2026 with many reasons to worry and with a question that can no longer be postponed: Was it a mistake to keep giving President Prabowo Subianto the benefit of the doubt? Or is it time for civil society groups, opposition figures and political parties to stop waiting for reassurance and instead remind the President that the country is heading down a dangerous path, however one chooses to frame it?

In the meantime, should they begin thinking seriously about whom they will support to challenge the incumbent in 2029 and how they might actually win?

When Prabowo was elected, even his harshest critics, including those most alarmed by his dark past, reluctantly granted him a pause. After all, there was no denying a basic democratic fact: The voters chose him. But being elected president does not grant a blank check, and legitimacy is not a permanent asset; it must be renewed through conduct, not assumed as a one-time inheritance.

For much of Prabowo’s first year in office, many Indonesians chose to interpret troubling signals as isolated cases rather than part of a larger pattern. The militaristic tone was dismissed as mere style, the growing presence of uniformed figures in civilian governance was framed as discipline and the appointment of visibly incapable officials was excused as political compromise, while the recentralization of state assets and revenues was sold as efficiency.

Together, however, they form a far more unsettling picture: democratic setback through accumulation rather than rupture.

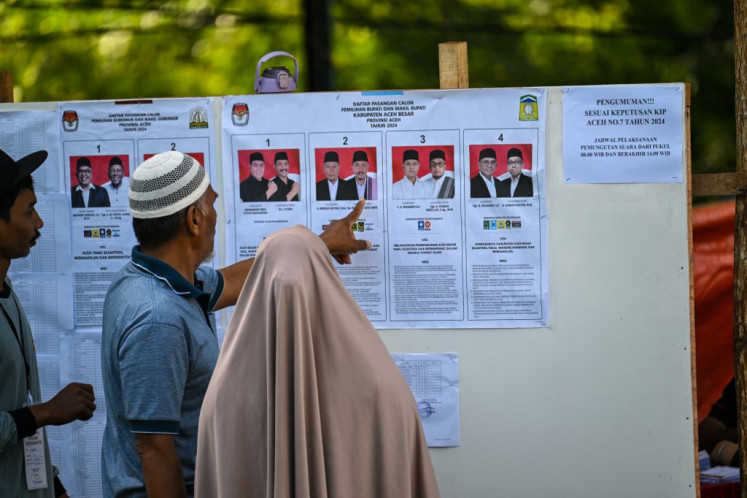

The clearest signal came when the President and a majority of political parties publicly expressed agreement to roll back direct elections for governors, mayors and regents and return their selection to regional legislatures (DPRD). Direct elections, the argument went, were expensive, chaotic and corrupt. But instead of cleaning up the system and enforcing the law, the decision was to remove voters from the equation altogether.

Indonesia has already lived under such a system. Corruption did not disappear; it simply moved behind closed doors. Bribes were paid, not to millions of voters but to dozens of legislators. Accountability shifted upward to party elites rather than downward to citizens. The process became cheaper, quieter and far easier to control.