Innovation: What Indonesia can learn from Taiwan, China

In a collective-exclusive society like Indonesia, disruption is hard because it means crossing status lines and shaking up patron-client networks.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

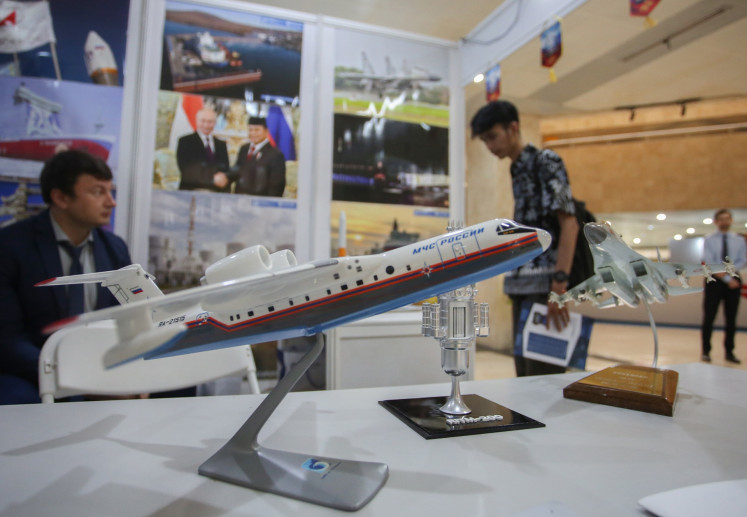

Tech breakthroughs: A visitor checks on a model of a fighter jet manufactured by a Russian manufacturer during a defense technology exhibition on April 21 at the BJ Habibie Science and Technology Complex in South Tangerang, Banten. Representatives from Russia, China, India and other countries participated in the exhibition that was organized by the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and the Defense Ministry to showcase innovation and research in the defense sector. (Antara/Muhammad Iqbal)

Tech breakthroughs: A visitor checks on a model of a fighter jet manufactured by a Russian manufacturer during a defense technology exhibition on April 21 at the BJ Habibie Science and Technology Complex in South Tangerang, Banten. Representatives from Russia, China, India and other countries participated in the exhibition that was organized by the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and the Defense Ministry to showcase innovation and research in the defense sector. (Antara/Muhammad Iqbal)

A

cross Asia, innovation doesn’t follow a one-size-fits-all formula. Taiwan’s relational autonomy, China’s directive cohesion and Indonesia’s collective-exclusive patterns show that success depends not just on ambition, but also on aligning cultural assumptions with system structures.

When people speak of culture, they often point to artifacts. In Taiwan, these artifacts are loud and clear: People queuing in silence, city gardens woven into dense urban space, spotless public toilets, respected pedestrian zones, clear waterways and a shared ethic of non-intrusion.

Even the choice not to replace functioning infrastructure with flashy alternatives reflects a deeper logic: Continuity over novelty, function over fashion. These patterns persist because they’re reinforced by quiet agreements about what’s right, expected and responsible. In short, artifacts endure because of shared values.

Taiwanese shared values, at the level of deep assumptions, center on three interwoven foundations: Relational harmony, pragmatic resilience and ethical responsibility within a collective frame. The emphasis on guanxi (social network) is not merely about networking but about sustaining mutual obligations across time.

Social adaptability arises from Taiwan’s geopolitical vulnerability and historical plurality, creating a cultural default toward compromise and long-term calibration rather than confrontation. Meanwhile, ethical restraint, which is often coded in Confucian, Buddhist and democratic civic vocabularies, grounds public trust and interpersonal conduct.

These are not declared ideals, but behavioral constants embedded in how decisions are made, how dissent is expressed and how ambiguity is managed.

Relational harmony in Taiwan goes beyond surface politeness. It is a strategic ethic of maintaining social continuity by managing face, avoiding confrontation and preserving emotional equilibrium in interpersonal ties.

The emphasis on guanxi is not about opportunistic networking, as often caricatured in China, but about mutual obligation sustained over time; built through consistency, reciprocity and emotional attentiveness.

This manifests in how Taiwanese society handles uncertainty: By adjusting strategies, modifying expectations and sustaining continuity through compromise rather than rupture. It stems from generations of navigating colonization, martial law, rapid industrialization and external political pressure; all without losing social balance. The mindset is: Survive first, adapt fast, improve gradually.

Ethical responsibility within a collective frame in Taiwan refers to the internalized sense that one’s actions must align with the well-being of the group, be it family, workplace or society. It is not about external enforcement or moral preaching, but about an ingrained duty to avoid causing loss of face or conflict.

This value is deeply influenced by Confucian traditions, but rearticulated in modern Taiwan through civic behavior, community-mindedness and even democratic participation. The individual is not erased but is expected to act in consideration of others.

Even in academia, these values shape everyday interactions. Professors can reach out to students as co-learners without losing authority, and without diminishing respect. The relationship is not flat, but humanized.

While Taiwan and China share Confucian roots, their shared values have diverged under radically different historical conditions. Taiwan builds its social order on decentralized trust, relational ethics and civic negotiation. Disagreement is not suppressed, rather it is managed through procedure, dialogue and mutual adjustment. Innovation tends to emerge from grassroots iteration, cross-sector partnerships and SME-led experimentation, not from national edict.

By contrast, China operates on a logic of centralized legitimacy, directive coordination and strategic consensus. Ethical responsibility is more vertical, often tied to loyalty to the state or organizational hierarchy.

Both societies are collectivist, but they enact collectivism differently. Taiwan practices relational autonomy: Individuals act with consideration for others but retain agency in navigating diverse norms. China emphasizes directive unity: Collective goals are clearly articulated, top-down and framed as national priorities.

At their core, both models function but through different control logics. Taiwan coordinates softly, bottom-up and absorbs dissent. China coordinates firmly, top-down and emphasizes speed and alignment. One builds pluralistic consensus; the other delivers directive efficiency.

Neither is inherently superior, but they are structurally incompatible.

This isn’t abstract. As a former vice president in one of China’s oil and gas subsidiaries, I saw firsthand that shared values aren’t about right or wrong, rather they are about fit.

In China, execution aligns tightly with hierarchy, and clarity often overrides consultation. It works because the system is designed to deliver that way. The real challenge isn’t importing ideals; it’s testing for cultural fit, execution discipline and systemic coherence.

Taiwan and China offer contrasting models; not moral alternatives, but operating systems.

Indonesia shares structural traits with China: A preference for hierarchy, status recognition and collective identity. Both operate as collective-exclusive societies, valuing group belonging, but with rigid in-group boundaries and vertical deference. In such cultures, command-based coordination feels natural, and China’s state-led innovation model can look attractive.

But this resemblance is misleading. China couples control with execution discipline; tight feedback loops, elite coherence and policy delivery mechanisms that ensure continuity. Indonesia lacks this executional backbone. Authority is often personalized rather than institutional; discretion replaces accountability. Imitating China without that coherence leads not to scalable innovation, but to bureaucratic sprawl and policy inflation.

Indonesia’s problem is not ambition, but alignment. The country doesn’t lack vision. It falls short of execution trust chains: Mechanisms that turn promises into outcomes.

In a collective-exclusive society, disruption is hard because it means crossing status lines and shaking up patron-client networks. Innovation stalls not from resistance, but because no one wants to absorb the relational risk of failure.

Across Indonesia’s universities, policy centers and pilot programs, many so-called innovation models are not functioning engines but showroom pieces. Built to impress donors or fulfill key performance indicators, they often lack the operational backbone to deliver.

These models are chosen not because they work, but because they’re easier. They demand less change and offer the illusion of progress through templates and shortcuts. But innovation can’t be simulated. It must be built, stress-tested and aligned with how people work and decide.

Real innovation requires discipline like the Navy SEALs and rebellion like pirates. Indonesia struggles with both. Discipline is uneven and rebellion is punished early. A student who questions is called “kurang ajar” (unethical), and a junior who insists on improvement is labeled “ngototan” (stubborn).

These aren’t neutral; they are cultural sanctions. In a society where pushing boundaries is seen as arrogance, not initiative, how can innovation happen? Not through slogans. Not through imported frameworks. Only when the system stops punishing those who try differently will innovation stop hiding.

Indonesia has the cultural instinct to coordinate, but not the systems to execute. If the country wants real innovation, not just pilot projects or policy theatre, it must build internal discipline, not borrow templates.

The question isn’t what worked elsewhere, but what fits here, with who we already are.

***

The writer is an alumnus of Harvard Business School and an affiliated alumnus of MIT Sloan School of Management.