Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTurning resource wealth into rules-based prosperity

Resource abundance alone is not destiny. Indonesia’s next challenge is to turn mineral wealth into sustainable, rules-based prosperity.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

s the world races toward net zero, a new geopolitical frontier is emerging, not over oil, but over critical minerals. Nickel, cobalt, copper, lithium and rare earths have become indispensable inputs for electric vehicles, solar panels and semiconductors. Whoever commands their production, processing and trade will shape the contours of the 21st-century economy.

Indonesia sits squarely at the center of this transformation. According to the US Geological Survey, Indonesia holds around 55 million metric tonnes of nickel reserves, about 42 percent of global reserves, making it the largest globally. The country also ranks amongst the top 10 producers of copper and bauxite.

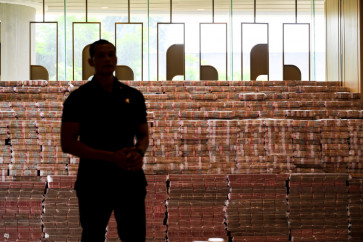

No longer content to remain a mere supplier of raw materials, Indonesia has adopted its hilirisasi (downstream industrialisation) policy, banning the export of unprocessed ores, establishing more than thirty smelters and attracting over US$30 billion in foreign direct investment between 2019 and 2023. Industrial parks such as Morowali and Weda Bay have become symbols of Indonesia’s ambition to build a full battery-manufacturing ecosystem, from mine to electric vehicle assembly.

Yet resource abundance alone is not destiny. Indonesia’s next challenge is to turn mineral wealth into sustainable, rules-based prosperity. Critical minerals are fast becoming “the new oil,” reshaping global trade and geopolitics. The multilateral trading system, designed in the post-war era, must now adapt to a world where access to minerals determines who commands clean-energy supply chains.

Three imperatives stand out.

First, transparency. Global mineral markets suffer from information asymmetry and price volatility. A WTO- or G20-led “Critical Minerals Data Hub” could help track production, trade restrictions and stock levels in real time, reducing uncertainty and deterring export hoarding.

Second, sustainability. Indonesia’s rapid industrialization has sparked environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns, from deforestation to coal-powered smelters. To remain competitive in high-value clean-tech markets, Indonesia must align with OECD-based environmental and social standards. Developing a national ESG certification and traceability framework would secure international trust and unlock green-finance flows from partners such as the United States EXIM Bank (Export-Import Bank of the United States) and DFC (US International Development Finance Corporation).